China’s Belt and Road Initiative Shifts Towards Smaller and Greener Projects

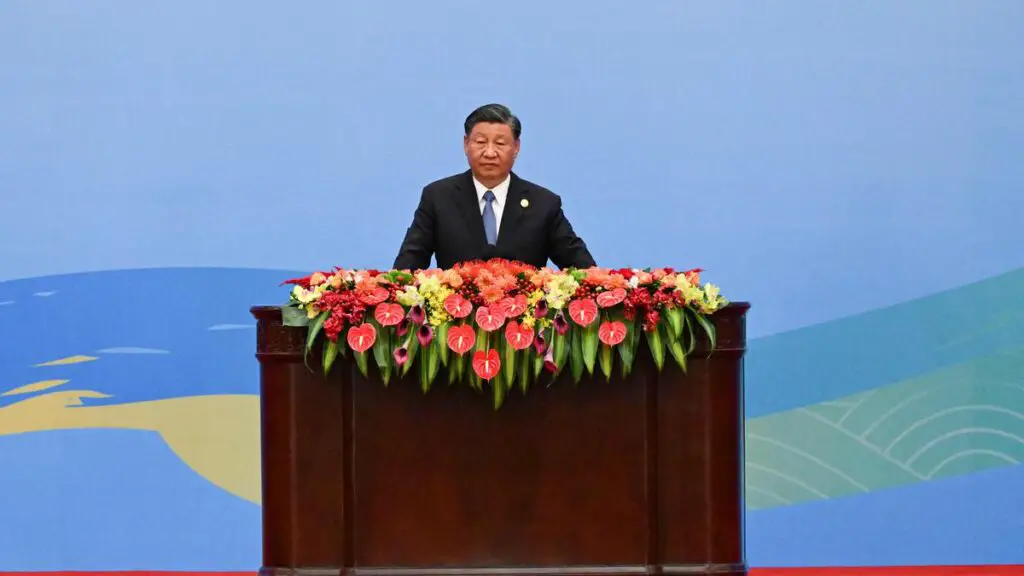

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is undergoing a transformation as the country looks to reduce the scale of its projects and address environmental concerns. After a decade of big projects that boosted trade but also left behind significant debts and raised environmental alarms, Chinese President Xi Jinping is leading efforts to make the initiative more sustainable.

The BRI has been instrumental in building power plants, roads, railroads, and ports around the world, while also strengthening China’s ties with Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. It forms a crucial part of President Xi’s vision to establish China as a major player on the global stage.

The initiative, known as “One Belt, One Road” in Chinese, was initially introduced as a program for Chinese companies to construct transportation, energy, and other infrastructure projects overseas with the support of Chinese development bank loans. The objective was to enhance trade and economic growth by improving China’s connectivity with the rest of the world, drawing inspiration from the ancient Silk Road trading routes between China and Europe via the Middle East.

The concept was first unveiled by President Xi during his visits to Kazakhstan and Indonesia in 2013 and has since catalyzed the development of significant ventures, including railroads in Kenya and Laos, as well as power plants in Pakistan and Indonesia.

A total of 152 countries have signed agreements with China to participate in the BRI. However, Italy, the sole western European nation to join, is expected to withdraw its support during the upcoming renewal in March next year. According to Alessia Amighini, an analyst at the Italian think tank ISPI, Italy has experienced a significant trade deficit with China since its participation in 2019.

China’s involvement in development projects under the BRI has positioned it as a major financier, on par with institutions like the World Bank. The Chinese government asserts that the initiative has launched more than 3,000 projects and mobilized nearly $1 trillion in investments.

The BRI has filled a void left by other lenders who redirected their focus towards areas like healthcare and education, while shying away from large-scale infrastructure development due to concerns about its environmental and societal impact. Kevin Gallagher, director of the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, highlights that Chinese-financed projects have encountered similar criticism, ranging from displacement of local populations to contributing excessive greenhouse gases that fuel climate change.

Chinese development banks have traditionally provided loans to finance BRI projects, and as a consequence, some governments have found themselves unable to repay the debt. This has led to accusations by countries such as the United States and India that China is engaging in “debt trap” diplomacy – purposely making loans that are destined to fail, enabling China to assert control over crucial assets. The Sri Lankan port, leased to a Chinese company for 99 years, is often cited as an example of this phenomenon.

Many economists argue that China did not intend to create such precarious loan scenarios, but instead learned from the resulting defaults. As a result, China’s development banks are currently scaling back their lending activities. Chinese development loans have already significantly decreased in recent years as China exercises caution in providing financial support to countries with high existing levels of debt.

Future BRI projects are likely to be characterized by smaller scales and a greater emphasis on environmental sustainability. Chinese investment in these projects by companies itself might become more prevalent than reliance on government development loans.

Christoph Nedopil, director of the Asia Institute at Griffith University in Australia, anticipates that China will continue to undertake some high-profile projects, including railways and oil and gas pipelines that generate revenue streams for repayment. An example of this is the recent launch of a Chinese high-speed railway in Indonesia, which garnered attention in both countries.

China has committed to ceasing construction of coal power plants overseas and is actively promoting projects that contribute to the global transition to greener alternatives. These initiatives encompass solar and wind farms, as well as factories dedicated to manufacturing electric vehicle batteries. However, concerns have arisen on the environmental impact of these projects, such as a large lithium-ion battery plant in Hungary, which is a BRI partner.

Overall, China’s Belt and Road Initiative is adapting to address the challenges it has encountered over the past decade. By focusing on smaller and greener projects, China aims to mitigate environmental concerns, improve sustainability, and ensure the long-term success of the initiative.